Understanding OSHA Deenergizing Rules

- Brian Hall

- Dec 9, 2024

- 4 min read

Lives Lost to Easily Preventable Hazards

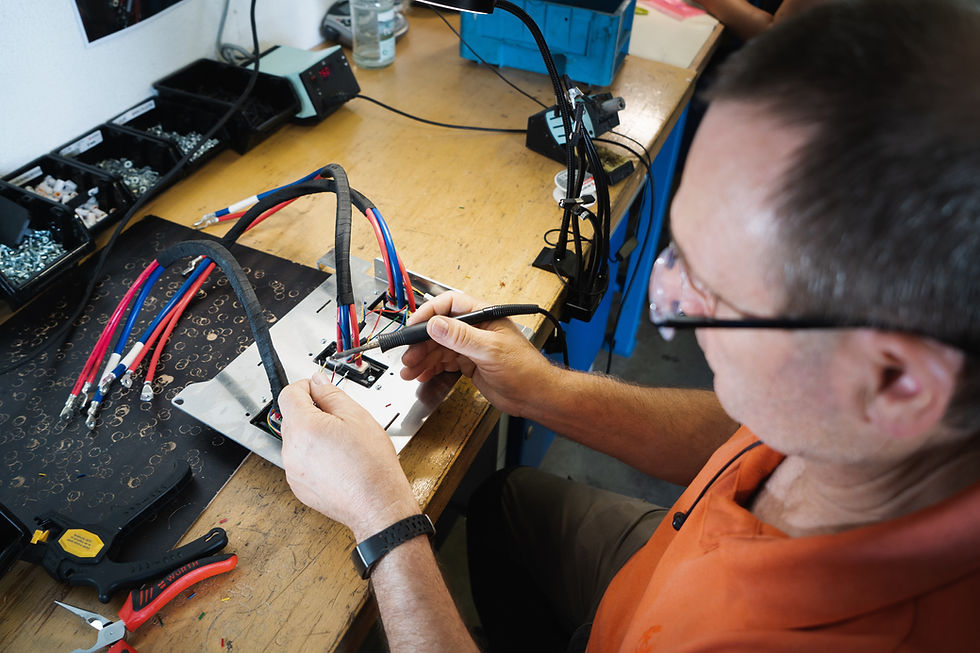

Reviewing OSHA accident data is a sobering reminder of the cost of not following safety rules. In one case, a worker pulling wire into an electrical cabinet made contact with a live wire, resulting in electrocution. Another tragedy involved an employee replacing a photocell in a wall-mounted light. The worker contacted an energized wire, fell from the ladder, and died after hitting his head on a concrete parking lot.

These stories are heartbreaking—and sadly, far too common. As electrical professionals, we are supposed to know better. Why, then, do these accidents happen? While the reasons can be complex, the solution is clear: too often, electrical workers fail to turn off power, exposing themselves to the risks of shock, electrocution, or burns from arc flashes.

The Rules Are Clear: Deenergize

OSHA’s regulations nearly prohibit work on energized circuits, with few exceptions. Failure to follow these rules too often results in injuries or fatalities, which are then made worse by citations for not locking and tagging out equipment. OSHA 1910.333 specifically addresses electrical lockout/tagout (LOTO), and its requirements go beyond general LOTO procedures. Electrical workers must also verify the absence of voltage and treat equipment as energized until verification is complete.

NFPA 70E, the gold standard for electrical safety, mirrors these OSHA requirements in Article 120: Establishing an Electrically Safe Work Condition and Article 110.4: Energized Work. While some may argue NFPA 70E lacks enforceability, it is the framework OSHA uses to evaluate safety practices after incidents. As such, following NFPA 70E is critical to avoiding citations and, more importantly, tragedies.

OSHA 1910.333(a)(1) states:"Live parts to which an employee may be exposed shall be deenergized before the employee works on or near them unless the employer can demonstrate that deenergizing introduces additional or increased hazards or is infeasible due to equipment design or operational limitations."

This means employees must deenergize electrical equipment unless rare, specific conditions are met.

Exceptions to the Deenergizing Rule

OSHA provides limited exceptions to the requirement to deenergize equipment before work. However, these exceptions come with strict conditions and are often misunderstood or misapplied. Here they are and what you need to know:

1. Additional Hazards or Increased Risk

OSHA Exception:Deenergizing may be avoided if shutting off the equipment introduces additional hazards or increased risk. Examples provided by OSHA include:

Interrupting life support equipment.

Disabling emergency alarm systems.

Halting ventilation in hazardous locations.

Eliminating critical illumination in an area.

Reality: These exceptions are rarely applicable in most facilities. For instance, life support systems and emergency alarms are often required by code to have backup systems, rendering this justification invalid. Employers must rigorously evaluate these risks to determine if deenergizing truly introduces a greater hazard.

2. Troubleshooting and Testing

OSHA Exception:Certain tasks, like measuring voltage or inrush current, cannot be performed without energized circuits. OSHA permits energized work when it is infeasible to perform the task with the power off.

What You Need to Do:

Recognize that troubleshooting is not a “free pass.”

Realize that troubleshooting frequently can be approached in different ways, often without the need to interact with energized equipment.

Follow OSHA 1910.333(a)(2), which mandates additional safety measures when working on energized circuits, including:

Insulated tools.

Barriers or shields.

Appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

Failing to follow these practices can lead to catastrophic outcomes.

3. Continuous Industrial Processes

OSHA Exception:Work on energized circuits may be allowed if shutting down equipment would disrupt a continuous industrial process, introducing increased hazards.

Clarification:This is another highly restrictive exception. According to OSHA’s 2006 Letter of Interpretation, the term "continuous industrial process" applies only when an orderly shutdown of integrated equipment would introduce greater hazards. Employers must evaluate this on a case-by-case basis and document their justification. Many production lines fail to meet this high standard.

4. Work on Low-Voltage Systems (<50 volts)

OSHA Exception:Live parts operating at less than 50 volts to ground do not need to be deenergized if there is no increased exposure to electrical burns or arc flash.

Key Considerations:While some low-voltage systems, like 24-volt control circuits, may meet this exception, others, such as industrial battery banks, can still produce hazardous arc flashes or burns. Employers must carefully assess the risks and determine if additional protective measures are needed. For example, even a car battery can create severe burns when mishandled—industrial applications carry similar risks.

Critical Reminder: Infeasible Is Not Inconvenient

OSHA is unambiguous about the distinction between “infeasible” and “inconvenient.”

Infeasible means the task cannot physically or operationally be performed without power.

Inconvenient includes excuses like production downtime or time-saving efforts, which are not valid justifications for working on energized equipment.

When in doubt, err on the side of safety. The stakes are simply too high to cut corners.

The Relationship Between OSHA and NFPA 70E

OSHA's electrical safety standards in Subpart S closely mirror the guidelines outlined in NFPA 70E. Specifically, a 2007 revision to OSHA 1910 subpart S incorporated language directly from Chapter 1 of the 2000 edition of NFPA 70E. This connection underscores that while NFPA 70E is not legally enforceable, following its safety recommendations often ensures compliance with OSHA's own electrical safety rules and regulations.

When OSHA investigates incidents, they look to NFPA 70E as the standard for evaluating safety practices. If you want to avoid OSHA citations—or worse, fatal accidents—apply NFPA 70E proactively. It is the definitive guide to safely working with energized equipment.

How Do We Stay Safe?

Provide Proper Training

Train workers to recognize electrical hazards, assess risks, and follow deenergizing procedures. Include supervisors and managers to ensure safety expectations are clear and consistent.

Establish Administrative Controls

Develop a written electrical safety program that defines clear guidelines for energized work. Require energized electrical work permits and strict authorization protocols.

Conclusion

The cost of ignoring these rules is staggering: injuries, fatalities, and shattered lives. Yet the solution is straightforward. Deenergize equipment whenever possible, train workers thoroughly, and follow NFPA 70E. OSHA’s rules were written for a reason—don’t let convenience or oversight lead to preventable tragedies.

Stay vigilant. Stay safe. Deenergize.

References:

OSHA-reported accidents: